Never did I imagine writing a post that would link my mom, Sue, with Dostoevsky, yet here I am. Doing just that. Let me explain, by starting with a quote from “The Brothers Karamazov”:

“A man who lies to himself, and believes his own lies, becomes unable to recognize truth, either in himself or in anyone else, and he ends up losing respect for himself and for others. When he has no respect for anyone, he can no longer love, and in him, he yields to his impulses, indulges in the lowest form of pleasure, and behaves in the end like an animal in satisfying his vices. And it all comes from lying – to others and to yourself.”

-Fyodor Dostoevsky, “The Brothers Karamazov”

My mom’s story, told in “Surviving Sue” is threaded with distortions galore. It’s complicated, but I don’t think that’s remarkable. It’s all about the nuances, the unfolding, and the reveal of a labyrinth of lies, told across nearly 300 pages. As I look back on the process of writing her story, I can’t think of much I would do differently if I were to start over. Darkness finds light…eventually. I just pushed the door ajar.

Beginning at the beginning was important. Sue’s early childhood pain and loss were central to the development of her personality and dysfunction.

I was challenged recently when someone asked me how I’d describe Sue in a sentence and this came to mind: “Sue always operated from zero, feeling she was unworthy.” It didn’t matter what decade of life she was in or the role she assumed, Sue’s inability to feel secure with herself drove most of her scurrilous, shameful behaviors and I believe those seeds were planted when she was just a young girl. Defenseless but scrappy, trying to find her way.

As her daughter and a frequent target of her venom, I carried pain for years but as I grew and began to layer the details into a composite – the broad landscape of Sue’s fractured life – I understood I was symbolic of her worst fear: Losing control. Not just the shaky hold she had over daily living but the assorted nebulous lies (bizarre, insignificant fibs and monstrous deceitful webs) that she so easily concocted. Sue worried I’d see the forest AND the trees. The whole damn topographical map of her dysfunctional heart.

Even now, do I fully understand? Gosh, no. But I dove in enough to see what drove Sue and that’s where empathy sat. Long before I was born, Sue carried pain in inescapable ways, not least of which was the guilt about my sweet disabled sister Lisa:

“Hiding the truth about Lisa’s birth along with her drug and alcohol use during her pregnancy was Sue’s most closely guarded secret. The layers added on later, about Lisa’s fabricated conditions, provided welcomed camouflage and alternative storylines. Not from malice. Sue needed the distractions to assuage her guilt and live, as much as she could, in the real world.”

-“Surviving Sue”, p. 293

I still have work to do as I consider Sue’s impact on my life. Writing about her? Cathartic? Yes, because I’m no longer afraid, but I still need to manage my exposure to the pieces of Sue’s story which reside in my home (and sometimes my head and heart):

“Right after Sue died, as much as I wanted to, I couldn’t examine everything in the “Sue trail.” Seeing her crazy-looking handwriting – scrawls and scribbles on scraps of anything and everything – summoned anxiety. Looking at those remnants, even now, is akin to confronting her all over again, across the years. Sue’s mania and madness are potent and palpable, jumping off the page and into my hands.”

-“Surviving Sue”, p. 291

Thank you so much for the interest in “Surviving Sue”, reading these snippets and/or purchasing the book or eBook. I’m grateful. And if you’ve read and feel inclined to write a review on Amazon, that would be lovely.

Vicki 😊

Portrait of Fyodor is by Vasily Perov from 1872

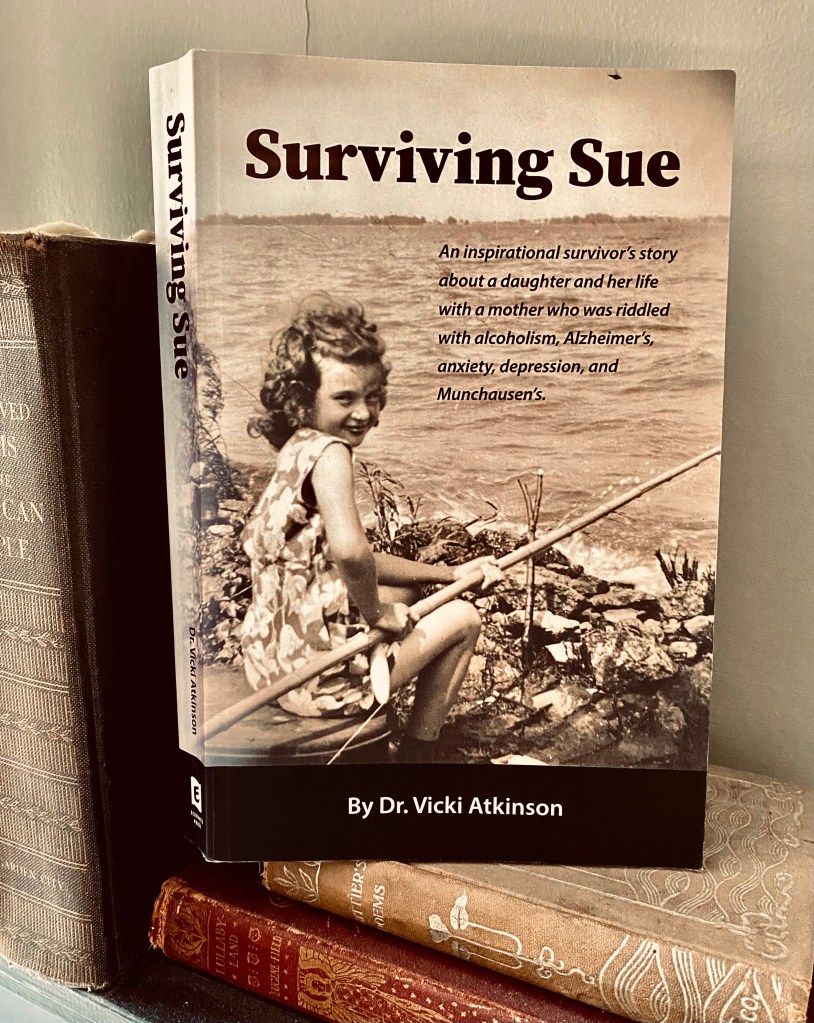

Family photo of Sue, the last time she fished with her dad in 1946

Leave a reply to E.A. Wickham Cancel reply